Abstract

Spiral Dynamics, a theory of human development based on Clare W. Graves’ emergent cyclical model, offers a valuable lens for rethinking general education curriculum design. This paper explores the application of Spiral Dynamics in curriculum development, arguing that educational content, pedagogy, and learning environments should align with the evolving value systems of learners. By integrating the psychological and cultural dimensions of human development into curriculum planning, educators can design more responsive and adaptive curricula. The paper outlines key characteristics of the Spiral Dynamics stages and proposes strategies for incorporating these insights into curriculum frameworks that foster holistic and transformative learning in K–12 settings.

Keywords: Spiral Dynamics, curriculum development, general education, value systems, educational psychology, integral theory

1. Introduction

In an age marked by rapid technological change, cultural diversification, and growing socio-economic disparity, general education systems face unprecedented challenges. The traditional education model—linear, rigid, and content-driven—often falls short in cultivating the adaptive, empathetic, and critical thinkers required for today’s interconnected world. Educational systems globally are being criticized for their inability to foster holistic development, civic responsibility, and meaningful engagement among learners. As such, curriculum developers are compelled to explore transformative models that respond to the complexities of individual psychological growth and collective societal evolution.

One promising framework for addressing this challenge is Spiral Dynamics, a theory of emergent value systems rooted in the developmental psychology of Clare W. Graves (1970, 2005). Unlike fixed-stage theories, Spiral Dynamics conceptualizes human development as a dynamic, non-linear process that evolves through a series of increasingly complex worldviews or “vMEMEs.” Each value system reflects not just cognitive development but also emotional, social, and existential dimensions of human experience. These systems are shaped by the interplay between personal growth and environmental conditions, including education, culture, economics, and social structures.

Applying Spiral Dynamics to curriculum design allows educators to align learning environments, instructional methods, and content with the developmental realities of learners. It offers a paradigm in which curriculum is not merely a sequence of content standards but a responsive, adaptive, and evolving structure that reflects the learners’ cognitive, emotional, and ethical growth. The value of such an approach is particularly salient in general education, which serves as the foundational experience for all learners and significantly influences their future engagement with society and lifelong learning.

Furthermore, the relevance of Spiral Dynamics in educational discourse aligns with contemporary movements in educational theory, such as transformative learning, constructivism, personalized learning, and integral education (Wilber, 2000). These movements emphasize that learning should be an active, meaningful, and reflective process that nurtures the whole person. Spiral Dynamics expands this notion by offering a nuanced typology of worldviews that can be directly mapped onto curriculum goals and instructional strategies.

Despite its potential, Spiral Dynamics remains underutilized in mainstream curriculum development, often confined to leadership, organizational change, and psychotherapy. This paper aims to bridge that gap by demonstrating how Spiral Dynamics can be operationalized in curriculum planning for general education. Specifically, it explores how the spiral’s stages can guide the formulation of learning outcomes, thematic content, and pedagogical strategies in ways that support both horizontal (skill-building) and vertical (consciousness-expanding) development. By doing so, it contributes to the emerging field of developmental curriculum design, which seeks to create educational experiences that are both contextually relevant and psychologically attuned.

In sum, the goal of this paper is to propose a practical and theoretical framework for integrating Spiral Dynamics into general education curriculum development. It argues that a spiral-informed approach enables educators to move beyond static curriculum models toward dynamic systems that prepare learners not just for employment or examinations, but for complex, ethical, and meaningful participation in a globalized and rapidly changing world.

2. Theoretical Background of Spiral Dynamics

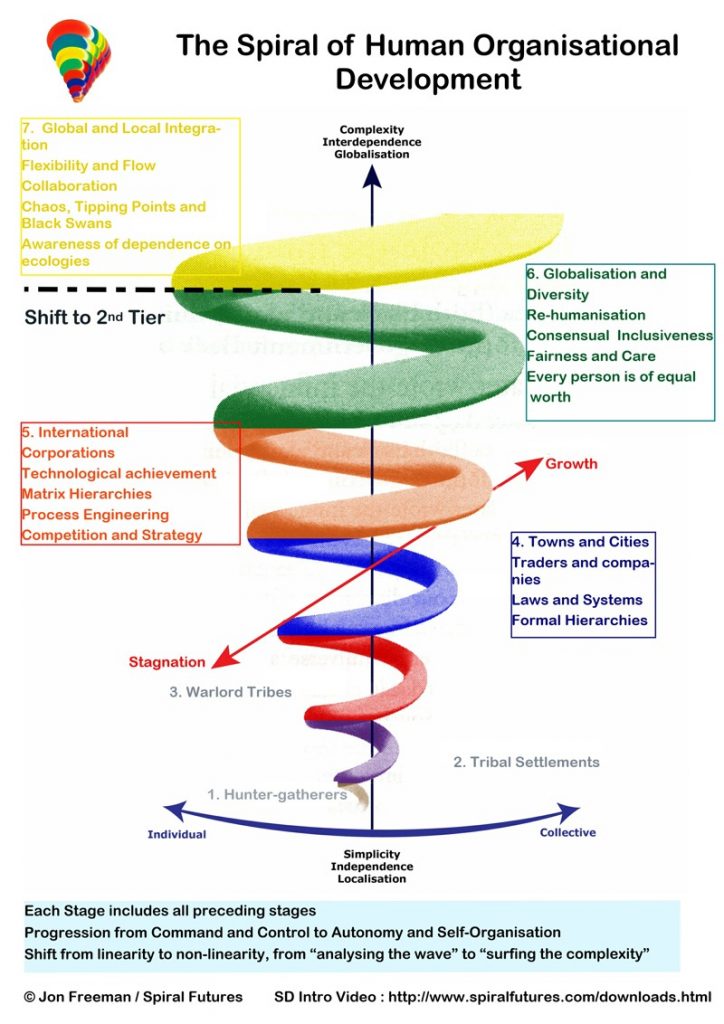

Spiral Dynamics is a theory of psychosocial development that emerged from the research of American psychologist Clare W. Graves during the mid-20th century. Graves (1970) sought to resolve apparent contradictions among prominent psychological theories by proposing an open-ended, emergent model of human value systems that unfold in response to life conditions. Rather than viewing human development as a singular linear progression (as in Piaget) or fixed by internal drives (as in Freud), Graves argued that humans evolve through adaptive intelligences—distinct ways of thinking, being, and valuing—that arise through the interaction between internal neurobiological capacity and external environmental demands.

Graves labeled his model the “Emergent Cyclical Double-Helix Theory of Adult Human Development”, emphasizing the dynamic interplay between changing life conditions and corresponding value systems. Following his death, this model was further developed and popularized by Don Beck and Christopher Cowan (1996), who coined the term Spiral Dynamics to describe the open-ended, evolving pattern of human development. Their work has influenced various disciplines, including organizational development, political theory, leadership studies, and-more recently-education.

At the heart of Spiral Dynamics is the concept of value memes or vMEMEs-deep structures of motivation, perception, and behavior that guide individuals’ worldview, decision-making, and relationships. These vMEMEs are not merely ideological stances but reflect a comprehensive psychosocial orientation. Each vMEME emerges in response to specific existential challenges, representing a solution to the problems of living at a particular level of complexity.

The model organizes these value systems into a color-coded spiral, with each level building upon the previous one while also transcending it. The spiral is generally categorized into two tiers:

First Tier (Subsistence and Surface-Level Change)

- Beige (SurvivalSense): Focused on basic survival needs-food, water, shelter, reproduction. This is a pre-rational, instinctive stage. Most relevant in infancy or contexts of extreme deprivation.

- Purple (KinSpirits): Tribalistic worldview centered around safety, tradition, rituals, and belonging to a protective group. Myth and superstition dominate.

- Red (PowerGods): Egocentric and impulsive, characterized by dominance, aggression, and personal power. Authority is based on strength, not structure.

- Blue (TruthForce): Absolutist and rule-bound, this worldview values discipline, duty, and moral certainty. It finds expression in religious orthodoxy, bureaucracy, and nationalism.

- Orange (StriveDrive): Strategic, achievement-oriented, and rational. Values competition, scientific progress, and material success.

- Green (HumanBond): Relativistic and pluralistic, emphasizing empathy, community, emotional intelligence, and egalitarianism.

Second Tier (Being-Oriented and Integrative Thinking)

- Yellow (FlexFlow): Systemic and integrative, this level recognizes the legitimacy of all value systems and adapts strategies accordingly. Focused on functionality, not ideology.

- Turquoise (GlobalView): Holistic and spiritually grounded, emphasizing interconnectedness of all life, global responsibility, and conscious evolution.

One of the unique contributions of Spiral Dynamics is its non-linear approach to development. Unlike strict stage theories, Spiral Dynamics allows for regression, stagnation, or simultaneous presence of multiple value systems within individuals or institutions. For example, a student might operate from an Orange mindset in academic settings but revert to Red in conflict situations. Likewise, an educational institution might espouse Green values in its mission statement but implement Blue policies in practice.

Another important feature is the double-helix structure, referring to the co-evolution of the individual and their environment. Development is not predetermined but triggered when the individual’s current vMEME becomes insufficient to solve life’s problems. This opens space for the emergence of a more complex value system.

In educational contexts, this means that curriculum and pedagogy must align not only with learners’ cognitive development but also with their evolving psychosocial orientations. For instance, expecting a Red-stage student to internalize Green-stage social justice curricula without adequate scaffolding may result in disengagement or behavioral resistance. Conversely, failing to challenge an Orange-stage student with complex, systems-level questions may lead to intellectual stagnation.

Educational scholars have drawn parallels between Spiral Dynamics and other developmental frameworks, such as Kohlberg’s stages of moral development, Piaget’s cognitive stages, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and Loevinger’s ego development theory. What distinguishes Spiral Dynamics is its emphasis on value systems as the mediating structure between cognition, emotion, and social behavior-making it particularly useful for curriculum developers seeking to create holistic and meaningful learning environments.

By recognizing that learners are situated at different stages along this spiral-shaped by culture, upbringing, trauma, and educational exposure-educators can design curricula that meet students where they are while guiding them toward more complex, integrative modes of understanding. This becomes essential in general education, which serves a diverse population and plays a foundational role in shaping civic identity, ethical reasoning, and lifelong learning habits.

In sum, Spiral Dynamics offers a robust theoretical foundation for reimagining curriculum development as a fluid, responsive, and ethically grounded process—an approach that reflects the diversity of human experience and the imperative of educational systems to cultivate adaptive, future-ready citizens.

3. Implications for Curriculum Development in General Education

Applying Spiral Dynamics to curriculum development in general education reorients the educational endeavor from a static, content-centered process to a dynamic, learner-centered, and developmentally aligned journey. Rather than assuming a uniform developmental trajectory or applying one-size-fits-all pedagogies, Spiral Dynamics prompts curriculum developers to consider the psychosocial worldview of learners—what they value, how they learn, and how they relate to others and to knowledge itself. This perspective is especially powerful in general education, where the goal is to provide foundational learning experiences for diverse populations across ages, cultural backgrounds, and developmental stages.

3.1 Curriculum as an Evolutionary Journey

Traditional curricula tend to emphasize the transmission of standardized knowledge and skills. Spiral Dynamics challenges this paradigm by positioning curriculum as a developmental scaffold—a structured yet flexible system that accompanies students on their personal and collective journey through the spiral of value systems. Each level of the spiral brings with it different motivations, perceptions of authority, social needs, and learning preferences. A spiral-informed curriculum does not simply aim to “cover content,” but rather to support learners’ movement from less complex to more complex ways of being and knowing.

This reconceptualization has profound implications for how curriculum is sequenced, assessed, and contextualized. Rather than linear progressions based on age or grade, spiral-aligned curricula might instead offer developmentally nested experiences, where thematic units are accessible at multiple vMEME levels and where learners are offered increasing complexity and autonomy as they demonstrate readiness.

3.2 Value-Sensitive Pedagogy and Instructional Design

Each vMEME level has distinct preferences for how learning is structured and delivered. Understanding these preferences allows educators to differentiate instruction in a psychologically congruent manner:

| Value System (vMEME) | Learning Style & Curriculum Preference | Instructional Strategies |

| Beige | Sensory, survival-based | Basic care routines, safety reinforcement |

| Purple | Magical, familial, story-driven | Use of legends, songs, rituals, group bonding activities |

| Red | Egocentric, competitive, dominance-seeking | Clear authority, high energy, immediate rewards |

| Blue | Orderly, moralistic, authority-driven | Structure, discipline, clear right/wrong frameworks |

| Orange | Rational, achievement-oriented | Goal-setting, debates, experimentation, STEM |

| Green | Relational, inclusive, emotional | Group work, consensus-building, social justice themes |

| Yellow | Integrative, self-directed | Independent projects, systems analysis, interdisciplinary learning |

| Turquoise | Holistic, contemplative, ecocentric | Global citizenship, mindfulness, ecological systems |

Example: Teaching a unit on “Communities and Leadership”

- Purple: Focus on community traditions and ancestors.

- Red: Identify strong leaders and heroic figures.

- Blue: Study the rules and laws of communities.

- Orange: Analyze how leaders achieve goals and succeed.

- Green: Discuss fairness, empathy, and group decision-making.

- Yellow: Compare different leadership models across societies.

- Turquoise: Examine how interconnected leadership affects planetary well-being.

This value-sensitive approach avoids cultural and developmental mismatches and fosters intrinsic motivation. It also helps educators resolve classroom conflicts that often stem from vMEME mismatches between teacher expectations and student worldviews.

3.3 Age-Stage Mapping: General Guidelines for Spiral Curriculum Design

While Spiral Dynamics is not age-bound, broad developmental patterns do correlate with stages of life. This allows curriculum designers to anticipate dominant vMEMEs in particular age groups, while also remaining sensitive to outliers.

| Educational Level | Typical Dominant vMEMEs | Curriculum Focus |

| Early Childhood (K–2) | Beige, Purple, early Red | Safety, belonging, imagination, sensory exploration |

| Lower Elementary (3–5) | Red, emerging Blue | Rules, fairness, heroes, consequences, social order |

| Upper Elementary (6–8) | Blue, emerging Orange | Responsibility, structured inquiry, competition, identity |

| Secondary (9–12) | Orange, Green | Achievement, critical thinking, collaboration, justice |

| Post-Secondary | Green, Yellow, some Turquoise | Complexity, systemic thinking, global ethics, integration |

It is important to remember that educational trauma, socioeconomic background, and cultural variation can delay or accelerate movement through these stages.

3.4 Multicultural and Inclusive Curriculum Design

Spiral Dynamics is particularly useful in multicultural and multilingual contexts, where learners may come from vastly different value systems. In these settings, imposing a singular worldview (e.g., a purely Blue/Orange, rule-bound, test-oriented model) can alienate students whose familial and cultural orientations are Purple or Red.

A spiral-informed curriculum acknowledges and validates all stages without judgment. It provides multiple entry points, encourages metacognitive reflection on value systems, and fosters cross-vMEME dialogue. This not only builds cognitive flexibility but also contributes to intercultural competence—a critical 21st-century skill.

3.5 Curriculum Content and Thematic Alignment

Using Spiral Dynamics, curriculum developers can map thematic content to different stages of learner development. This ensures that learning materials are both cognitively appropriate and emotionally resonant.

Sample Thematic Mapping for a Social Studies Unit: “Understanding Justice”

- Purple: Fairness in stories and family traditions

- Red: Revenge and power in myths and legends

- Blue: Laws and justice in historical civilizations

- Orange: Legal rights, court systems, rational arguments

- Green: Social equity, activism, human rights

- Yellow: Justice in complex systems, law reform

- Turquoise: Global justice, climate justice, indigenous sovereignty

Each unit can include layered activities for students operating at different vMEME levels, supporting differentiation and universal design for learning (UDL).

3.6 Spiral Dynamics as an Assessment Framework

Assessment in traditional curriculum models often measures only knowledge recall or skill demonstration. Spiral Dynamics invites more formative, developmental assessments that examine a learner’s evolving worldview, ethical reasoning, and systems thinking.

For example, reflective journals, dialogical assessments, ethical dilemmas, and portfolio-based evaluations can all serve as means to measure growth across Spiral stages. Educators might ask:

- At what stage is this learner approaching this task?

- What types of feedback will support their development to the next stage?

- How do classroom interactions reflect underlying value systems?

This reframing of assessment prioritizes transformation over performance and values inner growth alongside academic achievement.

3.7 Professional Development and Systemic Change

To implement Spiral Dynamics in curriculum development successfully, teachers and school leaders must receive targeted professional development that includes:

- Introduction to Gravesian theory and value systems

- Practical tools for diagnosing dominant vMEMEs

- Strategies for adapting instruction and managing value conflict

- Case studies and simulations for developing curricular interventions

Moreover, school culture must be examined through a Spiral lens. A school operating at a rigid Blue/Orange level may resist innovations aligned with Green or Yellow values. Thus, systemic change requires not only curriculum shifts but also organizational alignment with developmental diversity.

Spiral Dynamics offers curriculum developers a multi-dimensional lens for designing educational experiences that align with the evolving complexity of human values and consciousness. In general education, this approach supports inclusivity, adaptability, and purpose-driven learning. It allows learners not only to master academic content but also to understand themselves and others, navigate moral dilemmas, and engage responsibly with a changing world.

4. Practical Framework for Implementation

Translating Spiral Dynamics from theory into curriculum practice requires a systematic framework that accommodates the developmental diversity of learners while remaining aligned with institutional constraints and educational standards. This section offers a multi-layered implementation model organized around five key domains: (1) Spiral-Aligned Learning Objectives, (2) Curriculum Structure and Design Principles, (3) Pedagogical Practice and Teacher Competency, (4) Student Assessment and Evaluation, and (5) Whole-School Integration and Policy Alignment.

4.1 Spiral-Aligned Learning Objectives

The design of learning objectives is the foundational step in curriculum planning. In a Spiral Dynamics–informed framework, learning objectives must reflect not just content mastery but also value-system congruence and psychosocial growth. Objectives should be tiered to accommodate learners at different vMEME stages and scaffold their movement toward more complex thinking.

Examples: Spiral-Aligned Objectives for a Unit on Environmental Responsibility (Grade 8–10)

| vMEME | Sample Learning Objective |

| Purple | Describe family and cultural traditions related to nature and the land. |

| Red | Express opinions about environmental problems in your neighborhood. |

| Blue | Identify and explain environmental rules and regulations. |

| Orange | Research and present evidence-based solutions to reduce pollution. |

| Green | Evaluate different perspectives on environmental justice. |

| Yellow | Analyze systemic causes of environmental degradation and propose adaptive strategies. |

| Turquoise | Reflect on the interconnectedness of all life and design a community-based sustainability initiative. |

Guidance for Curriculum Designers:

- Frame objectives using verbs that match cognitive and affective dimensions of each vMEME (e.g., “follow rules” for Blue, “analyze systems” for Yellow).

- Offer multi-level objectives within each unit to allow differentiated instruction.

- Embed metacognitive prompts (e.g., “How has your thinking changed?”) to foster stage transition.

4.2 Curriculum Structure and Design Principles

A curriculum based on Spiral Dynamics should adopt a nested and layered design rather than a linear, sequential one. This allows educators to revisit core themes through increasingly complex lenses as students develop. This approach aligns with the spiral curriculum model proposed by Jerome Bruner (1960), but it incorporates value-systems awareness as the basis for progression.

Key Design Principles:

- Modularity: Design thematic units as standalone yet interrelated modules that can be adapted to different vMEMEs.

- Layering: Each unit should have a core layer (accessible to Purple-Blue), an analytical layer (for Orange-Green), and a systems-reflective layer (for Yellow-Turquoise).

- Resonance: Themes and materials should resonate with students’ lived experiences and cultural values.

- Progressive Complexity: Units must gradually introduce students to moral ambiguity, paradox, and systemic causality, supporting transition to higher-order thinking.

Example: In a curriculum on “Conflict and Peace,” early layers might explore playground conflicts (Red), rules of conflict resolution (Blue), while advanced layers examine historical peace treaties (Orange-Green) and nonviolent systemic transformation (Yellow-Turquoise).

4.3 Pedagogical Practice and Teacher Competency

Teachers are the bridge between curriculum intent and student experience. Therefore, a Spiral-informed approach requires pedagogical flexibility, developmental sensitivity, and the ability to recognize and respond to value-based behaviors in the classroom.

Core Teacher Competencies:

- vMEME Diagnosis: Teachers must be trained to identify the dominant value systems of learners through observation, language, emotional tone, and group dynamics.

- Instructional Flexibility: Teachers should know how to tailor activities for different vMEMEs within the same classroom (e.g., offering a storytelling task for Purple learners, a debate for Orange learners).

- Value Bridging: Teachers must mediate tensions between students or between students and curriculum when different value systems clash (e.g., Blue-rule learners vs. Green-consensus learners).

- Developmental Coaching: Teachers act as guides, supporting students through developmental transitions using reflective questioning, challenge, and support.

Professional Development Strategies:

- Workshops on Gravesian theory and classroom application.

- Reflective supervision using video footage to analyze value-system dynamics.

- Peer learning communities for teachers to share strategies.

4.4 Student Assessment and Evaluation

Assessment practices in most systems are heavily skewed toward content recall and technical skill mastery. Spiral-informed assessment practices extend beyond content to consider value-system expression, growth in perspective-taking, and developmental maturity.

Assessment Strategies:

- Formative Value Mapping: Regular reflection journals, classroom discussions, and teacher observations to map students’ vMEME expressions.

- Portfolio Assessments: Showcase student growth through artifacts that reflect different levels of meaning-making (e.g., narrative, analysis, systems thinking).

- Dialogical Assessments: Use Socratic seminars and peer interviews to assess reasoning and perspective-taking.

- Developmental Rubrics: Develop rubrics that assess not only skill levels but also developmental indicators (e.g., “Shows recognition of multiple viewpoints” as a Green marker).

Example: In a project on “Leadership,” students could submit:

- A personal story (Red),

- A rules-based leader profile (Blue),

- A scientific analysis of leadership styles (Orange),

- A group manifesto (Green),

- A systemic review of leadership trends across cultures (Yellow).

4.5 Whole-School Integration and Policy Alignment

Finally, systemic implementation of Spiral Dynamics requires more than curriculum reform. It demands organizational congruence, meaning that school culture, policies, discipline systems, and leadership styles also reflect developmental principles.

Steps Toward Whole-School Spiral Alignment:

- Leadership Training: School leaders should understand Spiral Dynamics and model integrative practices.

- School Climate Audits: Evaluate current policies through a Spiral lens. Is the discipline system Blue-punitive? Is the pedagogy Orange-performance driven? Where is flexibility needed?

- Integrated Student Services: Counseling, special education, and behavioral support systems should use Spiral-informed assessments to support students.

- Community Engagement: Work with parents and community stakeholders to recognize and support developmental goals across home and school.

- Policy Innovation: Advocate for broader policy changes (e.g., assessment reform, teacher autonomy) to support the spiral-aligned curriculum.

The practical implementation of Spiral Dynamics in general education is both feasible and urgently needed. It enables a responsive curriculum that meets students not just where they are academically, but where they are developmentally, emotionally, and ethically. By integrating value-sensitive objectives, flexible pedagogy, developmentally aligned assessments, and whole-school coherence, educators can cultivate learners who are not only knowledgeable but also wise, adaptable, and prepared to contribute to a complex world.

5. Discussion

The integration of Spiral Dynamics into curriculum development represents a paradigm shift from static, standardized models of education to a dynamic, value-sensitive, and consciousness-evolving approach. In this framework, curriculum is no longer a neutral collection of knowledge or merely a vehicle for achieving external standards; rather, it becomes a developmental tool that reflects and fosters the evolving inner landscapes of learners. This shift brings both compelling opportunities and profound challenges to general education systems.

5.1 Reimagining Curriculum as Developmental Ecology

Traditional curriculum frameworks often operate within what Spiral Dynamics identifies as Blue and Orange value systems. The Blue system emphasizes order, discipline, standardized outcomes, and centralized control, while Orange prioritizes individual achievement, meritocracy, and innovation. While these systems have contributed to institutional coherence and academic excellence, they tend to marginalize learners whose value systems do not align with them-such as students at the Red (assertive/impulsive) or Green (relational/egalitarian) stages.

A curriculum informed by Spiral Dynamics recognizes this limitation and introduces a developmental ecology, wherein each learner’s worldview is not judged but rather engaged, supported, and scaffolded. This ecological view aligns with recent trends in transformative education, integral theory (Wilber, 2000), and socio-cultural learning theories (Vygotsky, 1978), which emphasize the co-construction of knowledge, identity, and morality.

This approach supports not only horizontal development (skill acquisition, content mastery) but also vertical development (progression toward more complex, inclusive, and adaptive ways of making meaning). From this perspective, education becomes not simply a matter of preparing students for employment or national tests, but a civilizational project-the cultivation of mature, wise, and globally responsible human beings.

5.2 Addressing Educational Diversity and Equity

One of the most promising features of Spiral Dynamics is its capacity to redefine educational equity. Rather than aiming for uniform outcomes, a spiral-informed curriculum embraces equity of developmental access. That is, it recognizes that learners operate from different value systems based on cultural, socioeconomic, neurological, and familial factors—and that these systems influence how students relate to authority, knowledge, peers, and the learning process.

This framework offers a response to current debates on culturally responsive pedagogy and inclusive education. Instead of only accommodating surface-level cultural differences (language, food, festivals), Spiral Dynamics calls for a deep cultural responsiveness-one that takes into account the psychological and moral architecture of students’ worldviews. For example, refugee learners from collectivist Purple cultures may initially find Western Blue-Orange classrooms disorienting. Without sensitive curricular scaffolding that meets them developmentally, these students risk disengagement or misidentification as “behavioral problems.”

Furthermore, Spiral Dynamics can help educators de-pathologize developmental delays or misalignment, viewing them not as deficits but as reflections of adaptive responses to challenging environments. This insight opens space for trauma-informed and resilience-focused educational interventions.

5.3 Implications for Teacher Identity and Professional Growth

The successful application of Spiral Dynamics requires educators to evolve beyond content specialists into developmental facilitators. This shift can be both empowering and disorienting. Teachers accustomed to rigid instructional scripts and performance metrics may initially struggle with the fluidity and reflexivity required by a spiral-informed pedagogy.

However, the very implementation of Spiral Dynamics in schools can serve as a catalyst for adult development. As teachers encounter students with diverse value systems, they are invited to reflect on their own worldviews, biases, and pedagogical assumptions. Such reflection often initiates what Mezirow (1991) calls “perspective transformation”-a fundamental reorientation in how one sees themselves and their role in society.

Moreover, Spiral Dynamics provides a language of complexity and compassion that enables teachers to make sense of difficult classroom dynamics. Instead of labeling a student as “resistant,” “lazy,” or “non-compliant,” teachers can interpret these behaviors through the lens of value systems that may be misaligned with institutional expectations. This reframing foster empathy, adaptability, and pedagogical innovation.

5.4 Navigating Institutional and Political Barriers

Despite its theoretical elegance and practical promise, implementing Spiral Dynamics in formal education systems is not without challenges. School systems are often embedded in bureaucratic, industrial-era models that prioritize efficiency, uniformity, and accountability-values aligned primarily with the Blue and Orange vMEMEs. These models are generally averse to ambiguity, fluidity, and differentiation, which are essential features of spiral-informed curriculum development.

Introducing Spiral Dynamics may face resistance from educational stakeholders who interpret it as too abstract, relativistic, or “unscientific.” Policymakers may question its alignment with standardized testing regimes, and teachers may lack training or time to adapt their practices. Furthermore, misapplication of the model-such as rigidly labeling students by vMEME stage or using the model prescriptively rather than developmentally-risks reducing its transformative potential.

To address these barriers, advocates must emphasize the complementarity of Spiral Dynamics with existing educational goals: improved engagement, reduced behavioral issues, stronger teacher-student relationships, and more meaningful learning outcomes. Pilot programs, action research, and longitudinal case studies can provide empirical evidence of its efficacy.

5.5 Toward a Post-Industrial Educational Paradigm

Ultimately, Spiral Dynamics offers more than just a new method of curriculum design—it offers a new worldview for education itself. In a time of global upheaval, climate crisis, technological disruption, and social fragmentation, education systems must evolve to cultivate adaptive, integrative, and conscious citizens. A spiral-informed curriculum prepares learners not only to succeed in a competitive world but to navigate moral complexity, embrace diversity, and engage in systems-level problem-solving.

This represents a shift from a mechanistic model of education (students as outputs of instructional inputs) to an organic, systems-based model in which education nurtures the full spectrum of human development. In doing so, Spiral Dynamics aligns with emerging fields such as regenerative education, eco-pedagogy, and global citizenship education.

Spiral Dynamics illuminates the hidden scaffolding of human development-how values shape thought, behavior, and relationships. By integrating this model into curriculum design, educators can transform general education into a truly inclusive, developmental, and transformative endeavor. Yet, this transformation demands a courageous reimagining of roles, systems, and purposes within education. It calls on teachers, curriculum developers, and policymakers to act not merely as transmitters of knowledge but as catalysts of human evolution.

6. Conclusion

The application of Spiral Dynamics to curriculum development offers a profound reimagining of general education-one that positions human development, not merely content delivery, at the center of the educational experience. In contrast to traditional models that prioritize uniformity, external assessment, and standardization, Spiral Dynamics introduces a nuanced and flexible developmental map that recognizes the diverse value systems learners embody. It proposes that curriculum design must be responsive not only to age and cognitive ability but also to how learners make meaning, relate to others, and perceive their role in the world.

This developmental perspective compels a shift from viewing the curriculum as a fixed structure toward understanding it as a living system-adaptive, emergent, and contextually embedded. By incorporating Spiral Dynamics into curriculum planning, educators can design learning experiences that meet students where they are while encouraging progression toward more complex and integrative worldviews. In this model, education becomes both horizontally expansive-building skills, knowledge, and competencies-and vertically transformative, supporting students’ growth through stages of consciousness, identity, and moral reasoning.

The implications for practice are equally significant. At the classroom level, a Spiral-informed curriculum supports differentiated instruction, culturally responsive pedagogy, and social-emotional learning. At the institutional level, it enables more inclusive assessment frameworks, redefines professional development for teachers, and promotes a whole-school culture attuned to developmental diversity. At the policy level, it challenges education systems to reconsider the purposes of schooling, moving from compliance and competition toward compassion, creativity, and collective well-being.

However, the implementation of such a framework is not without its complexities. It requires educators to develop new competencies, school leaders to cultivate open systems thinking, and policymakers to support experimentation and flexibility. It demands a paradigm shift from technocratic management to developmental stewardship. Moreover, it calls for humility and critical reflection, acknowledging that value systems evolve contextually, not hierarchically, and that all stages have intrinsic worth and adaptive functions.

Yet, these challenges are outweighed by the opportunities Spiral Dynamics presents. In an age of global uncertainty, cultural polarization, and ecological crisis, education must do more than prepare students for employment or citizenship—it must cultivate in them the capacity for adaptive intelligence, empathetic action, and ethical systems thinking. These are precisely the qualities nurtured through a Spiral-informed curriculum that values developmental growth as a primary educational outcome.

In conclusion, Spiral Dynamics offers a robust, integrative framework for transforming general education into a truly human-centered endeavor. It invites educators to become developmental guides, curriculum to become a vehicle for consciousness evolution, and schools to become ecosystems of growth, inclusion, and meaning. As we look toward the future of education, embracing such frameworks will not only improve teaching and learning but will also help shape a more conscious, compassionate, and resilient world.

References

Beck, D. E., & Cowan, C. C. (1996). Spiral dynamics: Mastering values, leadership, and change. Blackwell.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education. Harvard University Press.

Graves, C. W. (1970). Levels of existence: An open system theory of values. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 10(2), 131–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/002216787001000205

Graves, C. W. (2005). The never ending quest: Clare W. Graves explores human nature (E. C. Beck & C. C. Cowan, Eds.). ECLET Publishing.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

Van Rensburg, H. J. (2012). Educational transformation: A spiral dynamics perspective. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(5), 804–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.10.007

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Harvard University Press.

Wilber, K. (2000). A theory of everything: An integral vision for business, politics, science, and spirituality. Shambhala Publications.